FAQ

What packs a 110-proof punch, is kick-started with a funky item called qu (‘chew’) and has an annual production that would fill 4,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools? Baijiu! Here is some background on baijiu and World Baijiu Day. followed by some key terminology.

What’s World Baijiu Day?

It’s an annual event held August 9 to promote baijiu, a Chinese alcohol that is pronounced “bye joe” and translates to “white alcohol”.

Baijiu is a clear spirit made from one or more grains and with a typical kick of 38 to 53 percent alcohol. It’s the world’s top-selling spirit.

World Baijiu Day is held August 9 in dozens of cities to give more people a chance to try this spirit. The date 8/9 translates to ba/jiu in Mandarin, sounding close to baijiu.

Here’s a two-minute primer on World Baijiu Day:

There is really that much baijiu produced!?

Baijiu represents about a third of global spirits sales. Annual production is around 10 billion liters per year and would take one hour to flow over Niagara Falls.

Then why haven’t I heard of it?

The vast majority of baijiu is produced and consumed in China. It’s used for holidays, business entertaining, gathering with friends and occasions likeweddings and Chinese New Year.

World Baijiu Day aims to make more people aware of this spirit through events in dozens of cities. Here is a map of the 2018 activities.

So how is baijiu made?

It’s a diverse category. From Mom ‘n’ Pop outfits to huge operations with national distribution, China has thousands of distilleries.

They can use one or multiple grains to make baijiu. Sorghum is the top candidate, although rice, corn, wheat and others are used, too.

Fermentation is done everywhere from buried clay jars to centuries-old earth pits. And the process depends on qu—pronounced ‘chew.’

You mentioned that earlier. What is qu?

Some people equate qu with yeast but it’s more complex. It’s a brick of compressed grains that is aged in a hot humid room and emerges loaded with fungi, bacteria and yeast.

When added to grain, it kicks off a two-step process of turning starches into sugar, and then sugar into alcohol, while influencing the ultimate flavor. It’s quite special.

What does baijiu taste like?

Reviews range from palatable to nail polish-esque. It really depends on the kind of baijiu you try—and your background and tastes. Here are three main styles in one sentence each.

Sauce aroma, associated with southwest China and particularly Guizhou province, tends to be funky—think soy sauce, savory herbs, stinky feet, umami—and complex.

Strong aroma, linked with Sichuan, is fruitier—lots of tropical character—and more phenolic, with a cleaner but just as potent and sophisticated body.

And light aroma, from the north, is simpler and milder—popular sub-categories include fenjiu, associated with Shanxi, and erguotou, very common in Beijing.

Again, each person’s background and taste will impact their experience of baijiu. So will the way in which they taste it. Some people are initially turned off baijiu because they tried it ganbei-style.

What’s that?

Ganbei is a toast that translates to “dry glass” and means “bottoms up”. Newcomers who knock back dozens of high-proof lukewarm shots don’t tend to fall in love with baijiu at first taste. That’s why the informal theme of World Baijiu Day is ‘beyond ganbei.’

So, basically sipping it rather than shooting it?

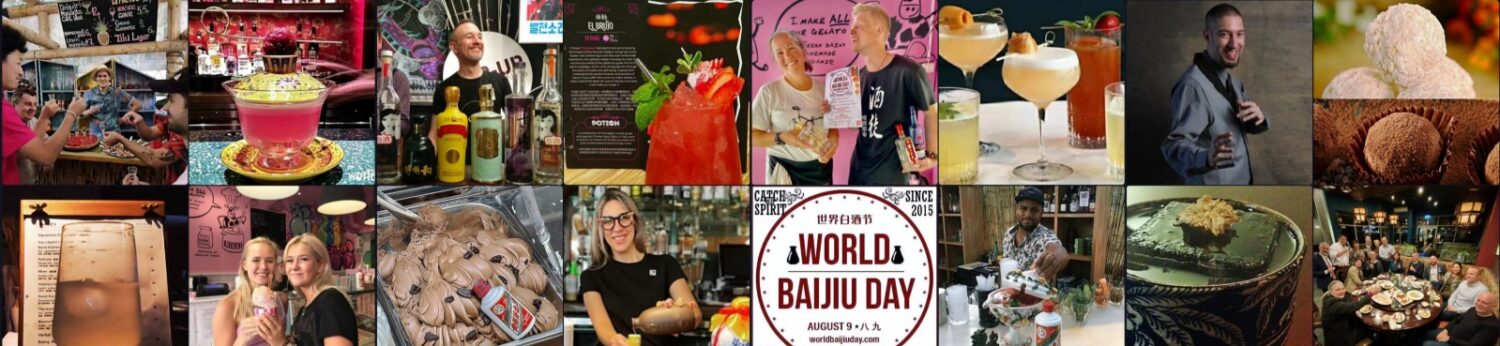

It means making baijiu accessible in creative ways. Some venues feature cocktails, infusions and liqueurs. Others do seminars, food pairings, or tasting flights that allow people to try different styles side by side. Some even use baijiu as an item in foods, like chocolate, pizza and gelato. One chef deep-fried it. Another did deep-fried baijiu ice cream.

And these events are held all over the world?

Yes, in over 50 cities since 2015. There are also baijiu brands with a focus on the world beyond China.

Some brands use baijiu sourced from China, such as Confucius Wisdom, Ganbei, HKB and Ming River. Others produce at home and label as baijiu, such as Vinn in the United States, Taizi in New Zealand, Dragon’s Mist in Canada, East Coast Baijiu and Australian Baijiu in Australia, Baijiu Society and Thompson’s in the UK, and more.

When are these events held?

World Baijiu Day is on August 9. This date sounds auspicious as it’s the eighth (ba) month and ninth (jiu) day—that sounds close to baijiu. But some venues prefer multi-day or even week-long events. Whatever the case, it gets even more people trying this interesting spirit!

TERMS

This section is a work in progress, based on info I’ve learned or gathered while organizing World Baijiu Day and from sources like Science Direct, Alcademics and Wikipedia. I’m sure I have a few things wrong but will work to expand this section and make it as accurate as possible.

Baigan

(白干 báigān) Another word for baijiu. Bai translates to white or clear, gan to dry.

Baijiu

(白酒 báijiǔ) A traditional Chinese spirit made through fermenting and distilling grain. Bai means clear or white, jiu means alcohol or liquor. Baijiu is the world’s most-consumed spirit, with production estimated at more than 10 billion liters per year. To get a sense of that amount, see here.

Daqu

(大曲 dàqū) Da means ‘big’ while ‘qu’ means starter. A paste of wheat, sometimes with barley and / or peas, is made into a paste, then shaped into bricks that are incubated in a warm / hot humid room for several weeks to months to acquire mold, bacteria and fungi. Funky!

The daqu is then pulverized and spread onto steamed grain before it goes into a fermentation container.

The bricks can be incredibly strong—pounding one with metal chair broke off not a single piece when making a Qu Brew for World Baijiu Day. We had to resort to a hammer.

Erguotou

(二锅头 èrguōtóu) Like fenjiu, a style of light-fragrance baijiu, popular in northern China and especially in the Beijing area. Erguotou translates to ‘second pot head’ and means second distillation. Better-known brands include Red Star (红星), Niulanshan (牛栏山) and Yidanliang (一担粮), all with entry level-bottles at less than USD2. Erguotou is a cheap way to get drunk.

Fenjiu

(汾酒 fénjiǔ) Like erguotou, it’s a style of light-fragrance baijiu. Sorghum-based, it hails from Shanxi province.

Fermentation

After the starch in grain breaks down into sugar, yeasts convert them to ethanol (alcohol) and carbon dioxide. it’s a two-step dance: glycosis sees yeast turn sugar into pyruvate molecules, then fermentation sees those turn into two carbon dioxide and two ethanol molecules. It’s humbling but booze, including baijiu, is yeast’s leftovers.

Fuqu

(麸曲 fū qū) Like daqu and xiaoqu, fuqu (‘bran starter’) gets the whole saccharification and fermentation process going, though in this case usually for a particular style of baijiu: erguotou. Fuqu uses the fungus Aspergillus.

Ganbei

(干杯 gānbēi) The Chinese equivalent of “bottoms up”, it translates as “dry glass” or “dry cup.” It’s a crucial part of drinking culture in China and all kinds of status-oriented situations. Knowing who to ganbei and when helps sustain social harmony. It can also get you quickly wasted beyond belief and memory.

Grain

While sorghum is the most common grain for making baijiu, numerous other grains can also be included in the mix. Everything from barley and millet to wheat and corn. And, of course, rice. Sichuan brand Wuliangye (五粮液 Wǔliángyè) translates to ‘five grain liquid’. It puts the yay! in yè.

Kaoliang

A type of sorghum-based light-fragrance baijiu associated with the island of Kinmen. The Chinese word for sorghum is gaoliang (高粱 gāoliang).

Light-fragrance baijiu

(清香 qīng xiāng) Linked with north China, this baijiu style is sorghum-based and fermented in ceramic jars or, for industrial-level quantities, in far bigger receptacles. Fenjiu and erguotou are famous examples of this style. Compared to the process for sauce-fragrance and strong-fragrance baijius, making this style is fast and easy. Entry-level baijius of this style are cheap.

Paojiu

Baijiu infused with sugar and pretty much anything from fruit to chili peppers to Chinese medicinal ingredients to ants. Want to do your own? Check this out.

Qu

(曲 qū) ‘Qu’ means starter and its a crucial ingredient that initiates the dual processes of saccharification and fermentation in baijiu-making. Different styles of baijiu used different qu, from brick-like daqu to the rice-based xiaoqu to erguotou‘s friendly helper fuqu.

Saccharification

The breaking down of starch from grain, such as sorghum, into simple sugars that can be converted to alcohol by fermentation. When making baijiu, both processes happen simultaneously.

Sauce-fragrance baijiu

(酱香 jiàngxiāng) Linked with northwest Guizhou and southeast Sichuan provinces. Maotai is the best-known producer. “Sauce’ is appropriate as the odor evokes soy sauce, sesame, bean paste and other umami-esque smells. Sauce-fragrance baijiu uses sorghum as a base and goes through multiple cycles of fermentation, in brick-lined pits, and distillations. It’s a long and labor-intensive—almost Sisyphean—process.

Shaojiu

(烧酒 shāojiǔ) Another word for baijiu, meaning “fired” or “burned” liquor.

Sorghum

(高粱 gāoliang) The grain most associated with baijiu.

Strong-fragrance baijiu

(浓香 nóng xiāng) The style most prominent in China and most associated with Sichuan province. It can use one grain ( 单粮 dānliáng) or multiple grains (杂粮 záliáng). Famous brands include Jiannanchun (泸州老窖 Jiànnánchūn), Luzhou Laojiao ( 泸州老窖 Lúzhōu Lǎojiào) and Wuliangye (五粮液 Wǔliángyè).

Strong-fragrance baijiu uses continuous fermentation, a process where fresh grains are introduced to the pits alongside distilled grains for a new fermentation cycle. This is a never-ending—almost Sisyphean—process.